Private security can operate in various ways in society. Whether in a war zone, high-risk areas, or your children’s school, professionals perform roles aimed at mitigating risks and threats of varying magnitudes. In some cases, these professionals are known as mercenaries, hired by countries to perform tasks they cannot or do not want to undertake. In this text, we will explore the differences between some of these characters.

The UN Mercenary Convention employs the following definition:

A mercenary is any person who:

(a) Is specially recruited locally or abroad in order to fight in an armed conflict;

(b) Is motivated to take part in the hostilities essentially by the desire for private gain and, in fact, is promised, by or on behalf of a party to the conflict, material compensation substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of similar rank and functions in the armed forces of that party;

(c) Is neither a national of a party to the conflict nor a resident of territory controlled by a party to the conflict;

(d) Is not a member of the armed forces of a party to that conflict; and (

(e) Has not been sent by a state which is not a party to that conflict on official duty as a member of its armed forces.

A mercenary is also a person who, in any other situation:

(a) Is specially recruited locally or abroad for the purpose of participating in a concerted act of violence aimed at: (i) Overthrowing a Government or otherwise undermining the constitutional order of a state; or (ii) Undermining the territorial integrity of a state;

(b) Is motivated to take part therein essentially by the desire for significant private gain and is prompted by the promise or payment of material compensation;

(c) Is neither a national nor a resident of the State against which such an act is directed;

(d) Has not been sent by a State on official duty; and

(e) Is not a member of the armed forces of the State on whose territory the act is undertaken.

According to El Mquirmi (2022):

“Despite the growing attention paid to PMSCs in the last few years, there is still a lack of information about what these companies really are, how and in what legal framework they operate, and for what purposes they are hired. Most of the literature is descriptive, focused on individual companies or single conflicts in which these companies have been involved. In reports and media articles, these corporations have also been labelled as ‘mercenaries’, asserting the need to continue the literature debate on how PMSCs differ from mercenaries. Authors and international organizations have considered PMSCs and mercenaries to be similar actors. The United Nations General Assembly, for example, considered PMSCs as “new modalities of mercenaries” (2007: 69), while Adams (1999), Musah and Fayemi (2000: 22-25), and Spear (2006: 16-19), claimed that despite PMSCs forming a corporate organizational structure that has a long-term business interest, they are not as different from mercenaries (Petersohn, 2014: 195). Other authors have focused their research on establishing clear differences between PMSCs and mercenaries on one hand, and regular soldiers on another, and have argued that “mercenaries are fighters lacking close and immediate control by a legitimate authority” (Petersohn, 2014: 195; Baker, 2011: 33; Percy, 2003)”

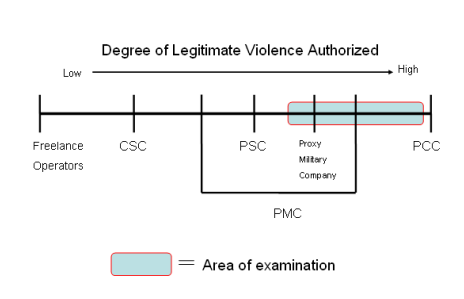

Private Combat Companies (PCC)

PCCs represent the epitome of professional mercenary organizations. They are private entities authorized to use lethal force and legally permitted to undertake proactive, offensive operations to neutralize threats. Typically, PCCs are self-sufficient, possessing all necessary weapons, equipment, and personnel within their organization. Members of PCCs are not citizens of the country that employs them but are granted visas under legitimate contracts with the government. A prime example of a PCC is Executive Outcomes, a foreign corporate entity hired to engage in military operations on behalf of another nation, although Executive Outcomes may argue that their actions serve a greater purpose beyond mere profit. It’s important to note that the causes or enemies faced by the employing country are not necessarily aligned with those of the PCC. While the U.S. government doesn’t directly employ PCCs, these organizations represent one end of the spectrum of outsourced security solutions.

Private Military Companies (PMC)

PMCs is a broad term encompassing any private corporation operating in combat zones or conflicted areas. Unlike PCCs, PMCs do not engage in proactive, offensive operations but are authorized to use lethal force when necessary. The legal authorization for PMC operations comes from the hiring government, typically limited to mobile defensive operations aimed at protecting specific targets. PMCs engage in various operations ranging from security to training and military advising. For example, Blackwater serves as a typical PMC, providing a versatile organizational solution to fulfill quasi-military needs that the U.S. military might be unwilling or unable to meet.

Proxy Military Companies

Proxy military companies are PMCs with strong ties to their home countries. They accept contracts aligned with their nation’s strategic objectives. Proxy forces bolster existing military capabilities and gain legitimacy by aligning with national interests. While they may or may not engage in direct force, proxy companies always seek explicit permission from their home nation before accepting contracts involving the application of force. A notable example is MPRI, whose senior staff comprises retired generals with close ties to Washington, closely aligning their actions with U.S. foreign policy.

Private Security Companies (PSC)

PSCs focus on site and personnel security, authorized to use deadly force to protect individuals, facilities, and government property. However, they do not engage in mobile defensive operations. PSCs typically train local personnel for security operations or provide personal site security for designated individuals. For instance, Armor Group operates as an active PSC in Iraq, training Iraqi Ministry of Justice security forces and providing limited personal security at fixed sites.

Commercial Security Companies (CSC)

CSCs specialize in industrial security at sites requiring armed guards, such as ports, logistical hubs, and airports. Unlike PSCs, CSCs are employed full-time by companies, rather than on a contractual basis. Their operations focus on static, defensive postures, including perimeter security and other services like rescue operations and fire services.

Freelance Operators

Freelance operators are individual mercenaries operating without formal allegiance or legitimate connections to the nations that hire them. Unlike PCCs, they lack authority to conduct military operations and typically operate outside established corporate structures. The term “freelance operators” euphemistically refers to modern mercenaries, with the UN providing guidelines for distinguishing between legitimate private security businesses and lone operators.

Although it is not a recent trend, the last three decades have seen the rise and the consolidation of PMSCs, mainly due to the rise of neoliberal ideals post-Cold War. Market forces have played an important role in changing how we understand security (Abrahamsen and Williams, 2011: 25-26). Globalization has broadened our understanding of security, and since the end of the Cold War, security has been understood as a business in a world dominated by globalization and market opening (Isenberg, 2008; Chesterman and Lehnardt, 2007). Neoliberal values have pushed states to analyze the costs and benefits of privatizing public services, and there was a certain enthusiasm in the 1990s for outsourcing government services, since it was considered more efficient and effective compared to what Robert Mandel (2002) called “bloated overcentralized government bureaucracies”. As Abrahamsen and Williams (2011) argued, “neoliberalism has acquired greater centrality in state policy, power has been redistributed in favour of elements of the state that are directly embedded in global structures […]. As a result, decisions are made increasingly in the context of global markets and global imperatives” (172). Therefore, security is perceived as a commodity, and has become a service like any other that can be bought from a marketplace. The reluctance of certain states to send their national armies to fight in conflicts, and the decision to outsource security, challenge the notion of state monopoly over the use of force, and also raise questions about state legitimacy and accountability.

El Mquirmi (2022)

Bibliography

O’Brien, J. M. (2008). Private military companies an assessment (Doctoral dissertation, Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School).

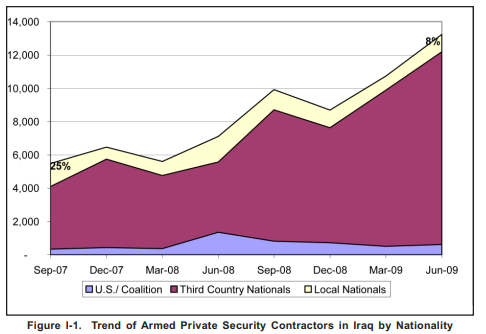

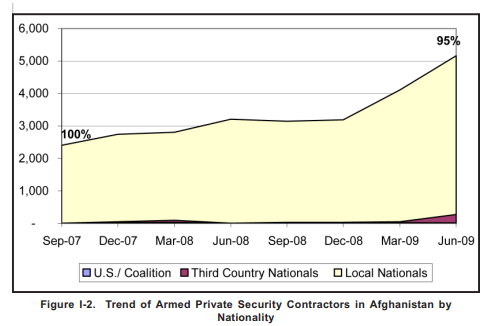

Command, U. J. F. (2010). Handbook for Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations. Suffolk, VA: Joint Warfighting Center. Available at http://www. scribd. com/doc/31126692/Handbook-for-Armed-Private-Sec-Contractors-in-Contingency-Ops. Accessed June, 2, 2010.

El Mquirmi, N. (2022). Private Military and Security Companies: A New Form of Mercenarism?

United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-convention-against-recruitment-use-financing-and

I am not sure where youre getting your info but good topic I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more Thanks for magnificent info I was looking for this information for my mission