Are you holding your pistol incorrectly?

Are you having trouble controlling the recoil?

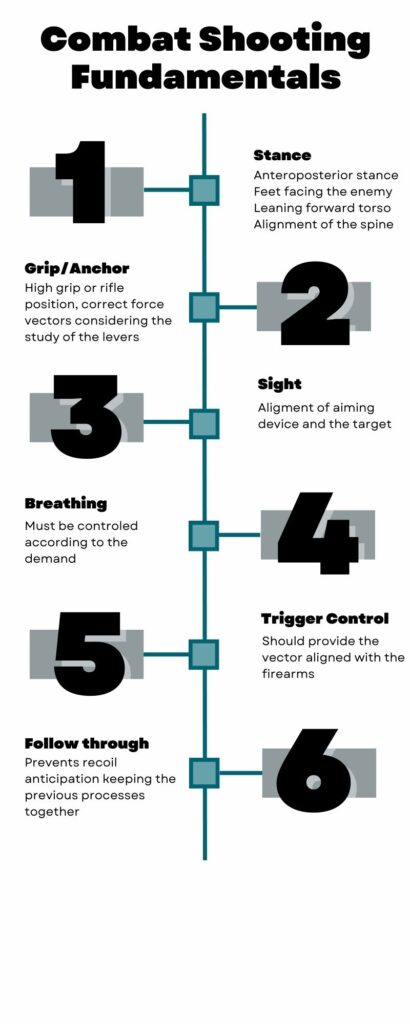

The fundamentals of shooting are stance, grip, sight alignment, breathing, trigger control, and technical follow-through, which should not be confused with tactical follow-through or scanning.

Each of these procedures has its execution objectives, which should always be carried out with a combat-oriented and efficient mindset.

Regarding grip, it’s the link between the shooter and the pistol. A good grip should maintain the firearm’s stability during sight alignment, allow for proper firearm function, and also mitigate recoil, with the latter being a noteworthy objective.

Controlling recoil is related to the ability to achieve good cadences. Considering that an enemy doesn’t have a physiological reason to cease being a threat after taking a shot (outside the central nervous system, at least), it’s important for those who use or intend to use their pistols for defense to be able to deliver multiple shots in a short amount of time against a defined target.

And here’s where the problem starts.

Grip techniques often create confusion in the minds of both novice and experienced shooters. It’s common to find larger individuals exerting a lot of force to grip the pistol tightly, yet the firearm remains loose, exhibiting significant recoil with each shot.

There are also those who quickly customize their pistols and indeed achieve impressive results. However, these customizations often act as a prosthetic support for deficiencies in executing the fundamental technique, rendering them entirely dependent on those modifications.

Let’s talk about the facts. What is a desirable cadence?

Cadence is the rate of fire that can be delivered against a specific target. Cadences against small and distant targets tend to be slower than cadences against larger and closer targets.

If we consider a human at urban combat distances (5-7 yards), we can consider good cadences as those with splits of 0.2-0.3 seconds. Sport shooters with customized firearms can achieve shorter intervals, while untrained individuals with firearms in their original configurations tend to have longer intervals or miss large, close targets when attempting this cadence.

Okay, and when are we going to talk about grip?

The development of grip techniques gained prominence during World War II. At the time, using both hands to hold a pistol was reserved for the more sensitive souls or women. The instructions of that era advocated aligning the barrel with the forearm while the left hand (for right-handed individuals) remained close to the chest, with no auxiliary function.

Over time, it was realized that the left hand could contribute to the grip, and several positions were tested. First, below the magazine, forming the so-called “cup and saucer” grip. In this grip, the left hand doesn’t contribute much, but the important thing is that it participates, right?

Continuing the biomechanical evolution, the left hand (support hand) was moved slightly higher, attempting to counteract the typical energy of recoil: when gripping a firearm with just the right hand, the standard recoil pattern of the pistol is upward and to the left.

We arrive at the end of the 20th century with a certain consensus among shooters: the thumbs-forward grip seemed to be the most efficient and was considered the state of the art.

However, even when using this grip, you would still find large shooters exerting circus-like forces against the pistol, struggling against their firearm, and achieving poor results. Why?

While the appearance of these grips may seem good to an inattentive observer, it’s not just about appearances; it needs to be effective.

Simply holding the gun with the left hand high is not enough. All force vectors must be applied to the upper part of the firearm, not the base of the grip. Otherwise, it’s like trying to hold a hammer by its handle’s end, meaning a great effort for an inefficient result.

The forces applied in a proper grip should be about torque, rotation, not just squeezing. Squeezing the grip of your pistol won’t help. All it does is hold the magazine. The real action happens at the top, at the chamber and the slide, where your efforts should be focused.

9x19mm caliber pistols don’t produce significant recoil. Anyone minimally trained should be able to achieve splits of 0.2 to 0.3 seconds with firearms of this caliber in their original configurations.

If you’re having trouble delivering such results, don’t blame the gun. Restructure your fundamentals.

See also: 7 factors that influence your cadence Infographic