An active shooter is an individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area. In most cases, active shooters use firearm(s) and have no pattern or method to their selection of victims, which creates an unpredictable and quickly evolving situation that can result in loss of life and injury. Other active shooter attack methods may also include bladed weapons, vehicles, and improvised explosive devices.

Homeland Security

Imagine finding yourself in a situation where you’re taking your kids for a day in the park, and suddenly, someone opens fire randomly on the crowd. What actions would you take? Now, consider your workplace or a school facility. Is there anything that can be done to prevent or mitigate such attacks?

You may have already heard about ‘run, hide, and fight’, but our goal in this text is to delve deeper into the topic, understanding, preventing, and effectively combatting these types of threats in the smartest way.

(1) Prevention

It is impossible to predict when an incident like this will happen. However, there are procedures you can follow to: (a) make a site less likely to be a target; (b) detect any threat as soon as possible; (c) make the attack less likely to result in a high number of casualties; (d) have a response plan; and (e) be prepared for the aftermath. Let’s delve into each one of these topics.

1.a. Make a site less likely to be a target

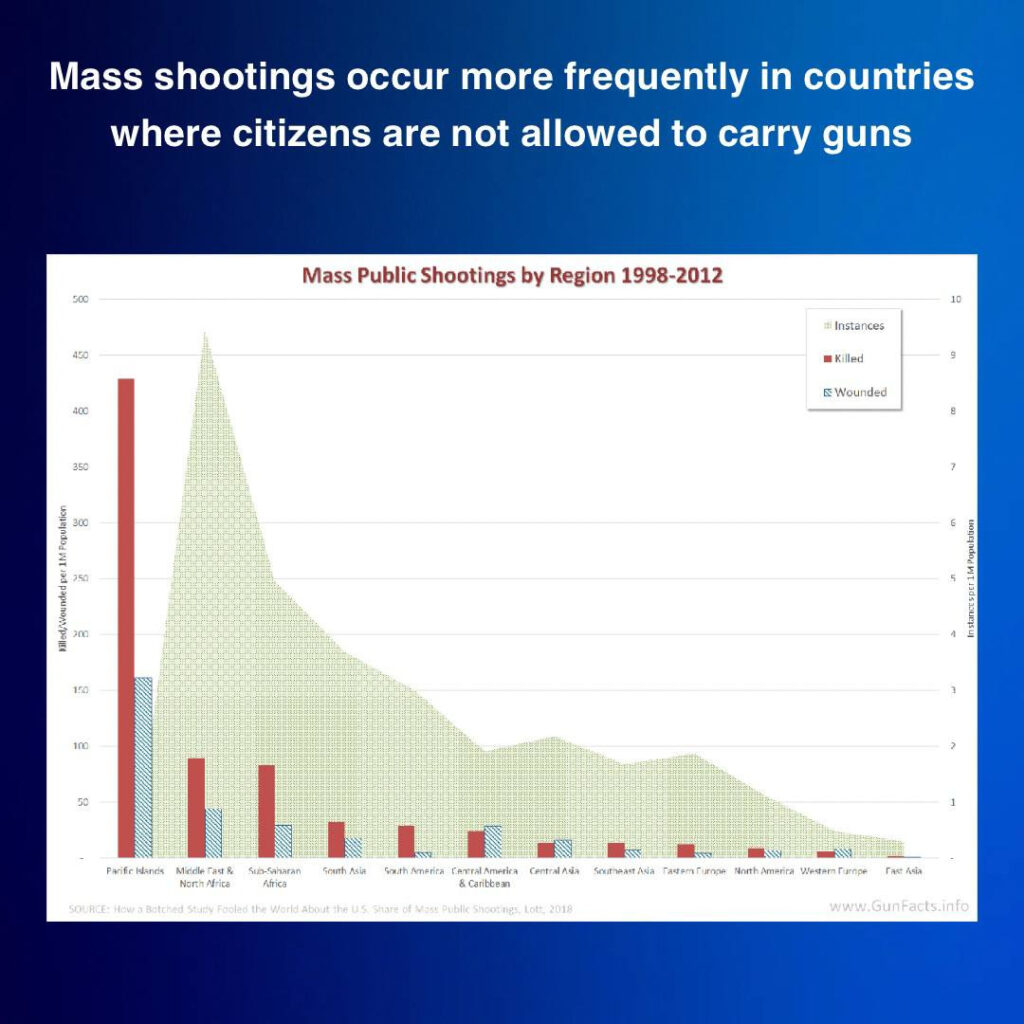

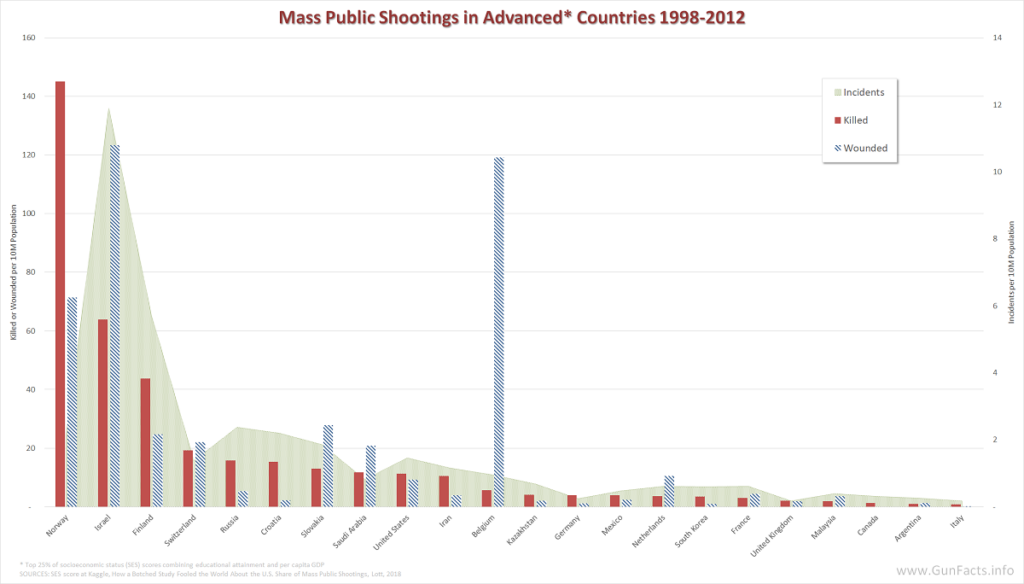

Active shooters intend to kill as many people as possible before someone stops them. This is why they rarely choose sites where people are likely to react, such as police stations, gun stores, or shooting ranges. Instead, they seem to prefer schools, malls, or other gun-free zones.

Make sure to let them know you are expecting them and ready to fight. Do not show weakness or fear, but strength and preparedness.

The number of casualties is related to how densely a space is occupied. Take care of the number of people you can accommodate, considering not only the legal requirements but also the safety necessities discussed below.

1.b. Detect any threat as soon as possible

Information is paramount for making the best decisions. When facing an attack, the sooner you detect the threat, the better you can organize your defense to prevent or combat it.

According to the Department of Homeland Security, there are indicators that one can use to identify potential violence by an employee.

Employees usually do not abruptly become violent but tend to exhibit signs of potentially aggressive behavior gradually. Identifying and acknowledging these behaviors can facilitate effective management and intervention. These indicators may encompass one or more of the following behaviors (please note that this list is not exhaustive, and it is not meant for diagnosing violent tendencies):

- Increased use of alcohol and/or illegal drugs

- Unexplained increase in absenteeism; vague physical complaints

- Noticeable decrease in attention to appearance and hygiene

- Depression / withdrawal

- Resistance and overreaction to changes in policy and procedures

- Repeated violations of company policies

- Increased severe mood swings

- Noticeably unstable, emotional responses

- Explosive outbursts of anger or rage without provocation

- Suicidal; comments about “putting things in order”

- Behavior which is suspect of paranoia, (“everybody is against me”)

- Increasingly talks of problems at home

- Escalation of domestic problems into the workplace; talk of severe financial problems

- Talk of previous incidents of violence

- Empathy with individuals committing violence

- Increase in unsolicited comments about firearms, other dangerous weapons and violent crimes

Human Resources’ Responsibilities

- Conduct effective employee screening and background checks

- Create a system for reporting signs of potentially violent behavior

- Make counseling services available to employees

- Develop an EAP which includes policies and procedures for dealing with an active shooter situation, as well as after action planning

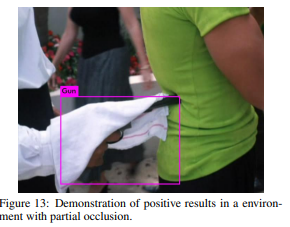

Furthermore, electronic security systems can assist individuals in the following ways:

- Detecting intrusions by individuals in areas where they are not authorized to be.

- Identifying attackers and the type of threat they pose.

- Locating the threat in real time.

- Notifying law enforcement and security personnel.

ABA Intl, for instance, can enhance your security systems, going as far as identifying individuals and even discerning whether they are armed or aggressive. However, this is a topic for another post.

1.c. Make the attack less likely to result in a high number of casualties

It is also important to construct facilities and train personnel to minimize casualties.

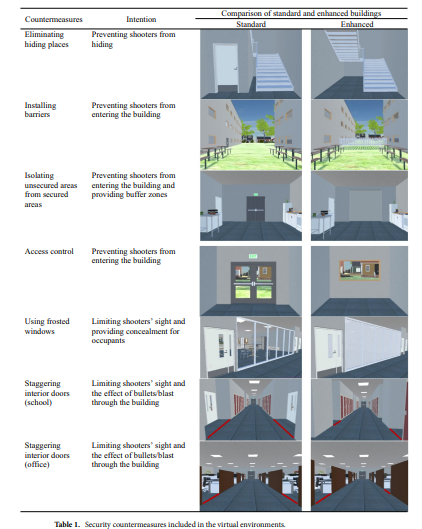

Zhu, Runhe, Lucas, Gale, Becerik-Gerber, Burcin, Southers, Erroll & Landicho, Earl. (2022) published de article titled “The impact of security countermeasures on human behavior during active shooter incidents“. The authors conducted virtual experiments aimed at assessing the effects of various countermeasures on human behavior in active shooter scenarios. A total of 162 office employees and middle/high school teachers were enlisted to respond to a simulated active shooter situation within virtual office and school environments, both with and without the implementation of multiple countermeasures. The results of the experiment revealed that these countermeasures significantly influenced participants’ response times and decisions, such as whether to run, hide, or fight.

Virtual experiments were conducted to empirically examine the impact of security countermeasures on responses to active shooter incidents. These experiments considered participants’ occupations as well as building and social contexts. The findings emphasized that certain security countermeasures intended to enhance building security might negatively affect responses to active shooter incidents. The emergency context and daily roles could also play a role in determining responses to such incidents. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of security countermeasures involving human behavior, roles, and emergency contexts is necessary to effectively enhance human safety. (Zhu et al, 2022)

Quoting Homeland Security:

“Facility Manager Responsibilities

- Institute access controls (i.e., keys, security system pass codes)

- Distribute critical items to appropriate managers / employees, including:

- Floor plans

- Keys

- Facility personnel lists and telephone numbers

- Coordinate with the facility’s security department to ensure the physical security of thelocation

- Assemble crisis kits containing:

- radios

- floor plans

- staff roster, and staff emergency contact numbers

- first aid kits

- flashlights

- Place removable floor plans near entrances and exits for emergency responders

- Activate the emergency notification system when an emergency situation occurs”

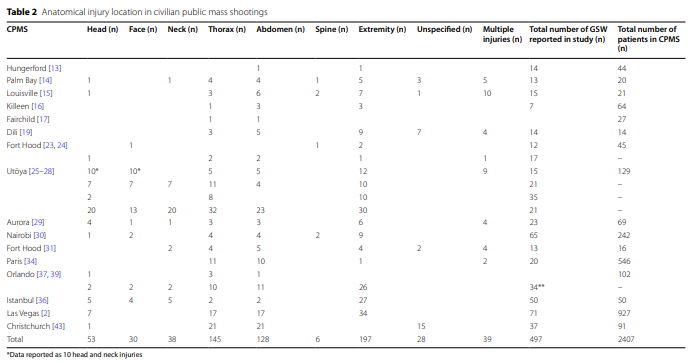

Smith, E. R., Shapiro, G., & Sarani, B. (2016) in the article The profile of wounding in civilian public mass shooting fatalities published at the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, conducted a review of 139 fatalities arising from 12 civilian public mass shooting (CPMS) events, with a total of 371 gunshot wounds. All wounds were attributed to gunshots, and victims averaged 2.7 gunshot wounds. In comparison to military reports, the case fatality rate was significantly higher, and the incidence of potentially survivable injuries was significantly lower. Notably, 58% of victims sustained gunshots to the head and chest, with only 20% having extremity wounds. In 77% of cases, the head or chest was identified as the probable site of fatal wounding. Potentially survivable wounds were observed in only 7% of victims, with the chest being the most common site (89%) for such injuries. None of the head injuries were deemed potentially survivable, and no deaths resulted from extremity-related exsanguination.

In a more recent study, however, Nyberger, K., Strömmer, L., & Wahlgren, C. M. (2023) found that the dominating anatomic injury location per event was the extremity followed by abdomen and chest.

Training personal to be able to stop massive bleeding and providing resources and gear for first responders can save lives.

STOP THE BLEED® is a crucial nationwide campaign in the United States, initiated by the American College of Surgeons, aimed at empowering individuals with the knowledge and skills to stop severe bleeding in emergency situations. This course provides invaluable training in hemorrhage control, including the proper use of tourniquets and wound-packing techniques. To bring this life-saving course to your facilities, you can get in touch with your local STOP THE BLEED® organization, which will help you arrange certified instructors (such as ABA Intl) and necessary resources. Ensuring that your team is well-prepared to respond to traumatic injuries can make a significant difference in saving lives during critical moments.

1.d. Have a response plan

Once you identify an ongoing attack, there are several actions that can be taken to minimize the damage caused by the assault.

“Components of an Emergency Action Plan (EAP)

Create the EAP with input from several stakeholders including your human resources department, your training department (if one exists), facility owners / operators, your property manager, and local law enforcement and/or emergency responders. An effective EAP includes:

- A preferred method for reporting fires and other emergencies

- An evacuation policy and procedure

- Emergency escape procedures and route assignments (i.e., floor plans, safe areas)

- Contact information for, and responsibilities of individuals to be contacted under the EAP

- Information concerning local area hospitals (i.e., name, telephone number, and distance from your location)

- An emergency notification system to alert various parties of an emergency including:

- Individuals at remote locations within premises

- Local law enforcement

- Local area hospitals”

1.e. Be prepared for the aftermath

Accoding to Floyd et al (2018), the timeline of victim assistance is categorized into three sequential phases with some overlap: short-term (from the incident through several days), intermediate (days to months), and long-term (months to years) recovery. Short-term recovery, beginning from the onset of the incident until several days after, encompasses various victim needs and services. The actions taken during this phase have a lasting impact on the overall recovery efforts. First responders, despite their training in active shooter response, often experience profound emotional and sensory stress when dealing with victims during such incidents. Integrating a disaster recovery coordinator early in the response process can aid first responders, who are also affected by the situation, in providing care to victims and preserving the crime scene. Additionally, the establishment of a reunification and notification center for victims and families has evolved to address the realities of higher casualties, with plans for compassionate death notifications coordinated by qualified individuals.

During the initial response, general information exchange, social media, and press involvement are inevitable. Efforts should focus on improving official communication channels to provide accurate and timely updates and instructions from a designated public information officer within Unified Command. The rapid nature of modern incidents and communication technologies highlights the importance of effective pre-planning, execution, and early prioritization of families and victims, ensuring they receive information before widespread public release. Avoiding media interference with the affected families and victims is essential, as seen in previous incidents where sensitive information was disclosed through media channels, causing unnecessary distress. Precautions should be taken to protect the privacy of those involved in such critical situations.

Floyd et al. (2018) describes that intermediate recovery spans the days and months following the incident, focusing on continuous support for victims and their families. They often find themselves overwhelmed and uncertain about navigating the next steps. To alleviate their distress, ongoing victim assistance comes into play, facilitating an assessment of their evolving needs and coordinating essential services, involving first responders and community members in the process. This phase often benefits from the involvement of trained victim services liaisons or advocates, who play a vital role in supporting victims and their families, including those hospitalized. This role may require close collaboration with mental and emotional health services and treatments. Several models from past incidents highlight the significance of such liaisons, including navigators employed in Boston after the 2013 marathon bombing, the creation of a Family Support Liaison by the Connecticut State Troops post-Sandy Hook, and the establishment of a family liaison program in Colorado following the 2012 Aurora theater shooting. Notably, these liaisons also assisted in managing media involvement.

The reunification and notification center can rapidly transform into a family assistance center (FAC), which offers ongoing support by providing necessary services and information, including mental health counseling, healthcare, childcare, crime victim compensation, legal assistance, travel arrangements, and financial planning for victims, family members, and first responders. While several aspects of the FAC may follow a standard procedure, a thorough needs assessment can identify real and potential physical, mental health, and emotional needs, especially for first responders, victims, and those affected by the event. Additionally, it helps pinpoint populations with access and functional needs that are unique to the situation. The example of the FAC set up at the Sikh Temple in Wisconsin after the 2012 shooting illustrates the importance of international coordination through the State Department, as well as the provision of language and culturally appropriate victim services to the affected families while preventing media intrusion. In another instance, specific victim services tailored to the LGBTQ community were necessary following the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting.

During the intermediate recovery stage, volunteer participation and donations may surge. Organizational planning for volunteer management, screening, training, and supervision is crucial to handle the influx of volunteers who may be called upon during emergencies. Onsite, a volunteer reception center can receive, organize, and direct volunteers, while protocols should be established for using untrained volunteers and for denying access to unqualified individuals. Depending on the incident, donations may become substantial. Organizations should prepare for the acceptance, control, receipt, storage, distribution, and disposal of donations, including monetary contributions and other donor requests. This effort, coordinated through the PIO, can leverage media channels to guide potential donors on how and what to donate. Ideally, this guidance should involve input from victims and their families. To handle monetary donations, a centralized donation system and site managed by an appropriate agency are recommended, similar to the approach taken after the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, where the Oklahoma City Disaster Relief Fund was initiated. Currently, the National Compassion Fund collects public donations to be directly distributed in future mass casualty crimes. The management of volunteers and donations may extend into the months or even years during the recovery process.

Additionaly, according to Floyd et al. (2018), long-term recovery extends over months and years following the incident, building upon the preceding stages, and may necessitate the establishment of a long-term recovery committee. This stage involves sustained considerations for long-term victim services and resilience as the community strives to recover. Victim liaisons continue their role in assisting victims and their families, including hospitalized victims, to ensure the fulfillment of their physical, emotional, and mental health needs. Approximately one week to over three months post-incident, the Family Assistance Center (FAC) could evolve into a Community Resilience Center (CRC), offering ongoing services, assistance, and supporting memorial activities. Like the FAC, the CRC must address access and functional needs populations and attend to symptoms of secondary and vicarious trauma experienced by response and recovery personnel. Managing volunteers and donations might continue during this stage, emphasizing the distribution and proper disposal of donated items. For instance, Newtown dealt with an influx of more than 65,000 teddy bears and half a million letters, necessitating extensive storage facilities and, eventually, the respectful incineration of these materials, referred to as “sacred soil.”

In this phase, coordination is essential to support local mental health services and substance addiction treatment, and behavioral health services are vital for victims (Jacobson, 2001). As legal proceedings unfold, victims and their families require assistance in retrieving personal belongings, preparing victim impact statements, managing media involvement, receiving support during trials, and staying informed about investigations and legal matters, including prosecution, adjudication, sentencing, and prisoner status, including parole hearings. Victims and their families should have access to incident hearings, criminal justice proceedings, victims’ rights, and possible security measures when entering or exiting courthouses or auxiliary facilities. Following the Oklahoma City bombing, Safe Havens played a crucial role in providing crisis counseling and serving as a support center for victims’ family members and survivors participating in trial proceedings in Denver or viewing televised trials in Oklahoma City (OVC, 2000). When victim needs persist, additional funding and a needs assessment may be required. Community leaders can identify, evaluate, and apply for direct financial assistance to meet the needs of individual victims, family members, local entities, and city, county, and state jurisdictions during the recovery phase. In numerous cases mentioned in this article, supplemental funding was provided to support victims through the Antiterrorism Emergency Assistance Program (AEAP).

(2) When SHTF

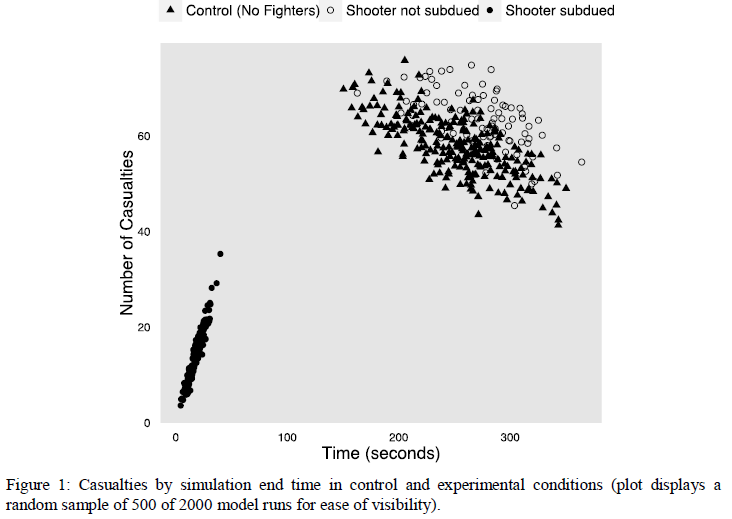

Thomas W. Briggs and William G. Kennedy published the article titled “ACTIVE SHOOTER: AN AGENT-BASED MODEL OF UNARMED RESISTANCE” in 2016. In their study, “an agent-based model (ABM) explored the potential for limiting casualties should a small proportion of potential victims swarm a gunman, as occurred on a train from Amsterdam to Paris in 2015” and their results suggest that even with a miniscule probability of overcoming a shooter, fighters may save lives but put themselves at increased risk.

As expected, a higher percentage of individuals taking action increases the likelihood of successfully subduing the shooter. When too few people engage, the chances of overcoming the shooter become minimal. By adjusting the proportion of the population participating in the response, we can significantly impact the probability of subduing the shooter. If only 0.1 percent of the population gets involved, the model indicates a very low success rate in subduing the shooter. However, when 0.4 percent join the effort, the shooter gets subdued in approximately half of the model runs. If the participation rate increases to a range between 0.8 and 1 percent, the shooter is successfully subdued in nearly all model simulations.

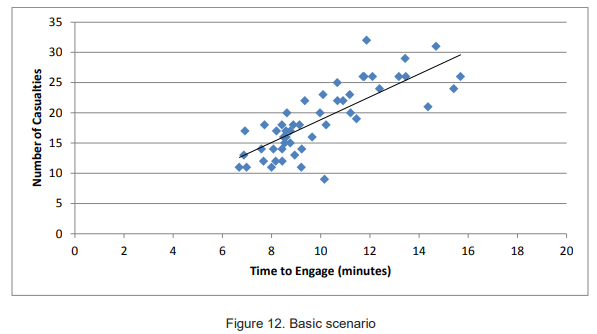

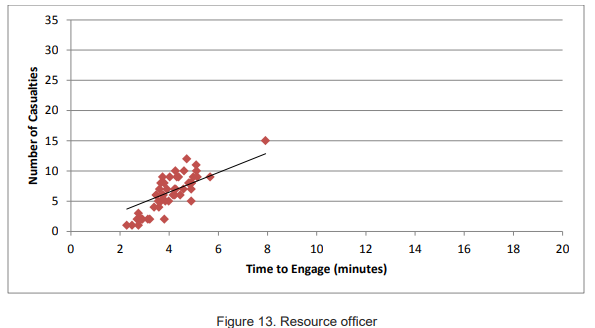

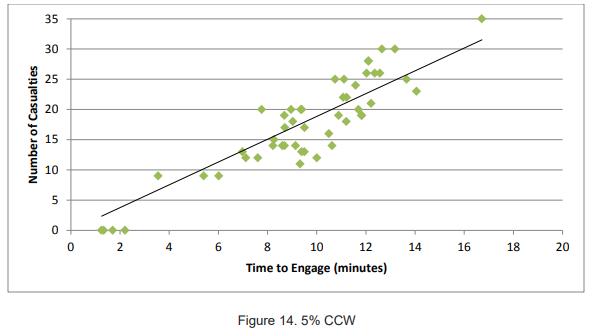

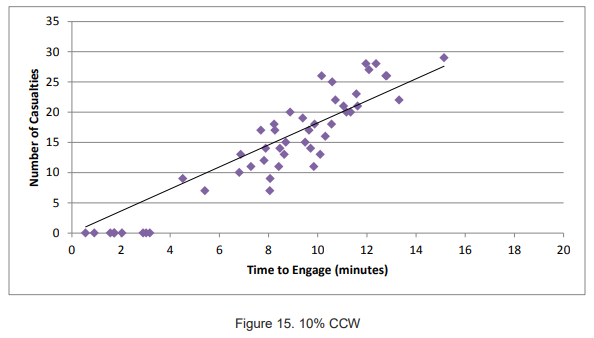

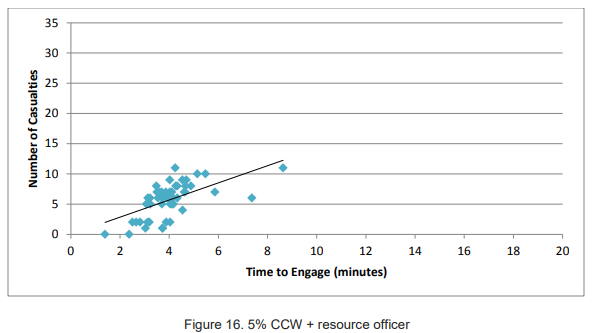

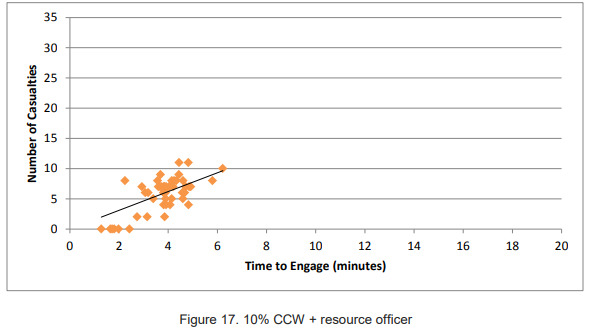

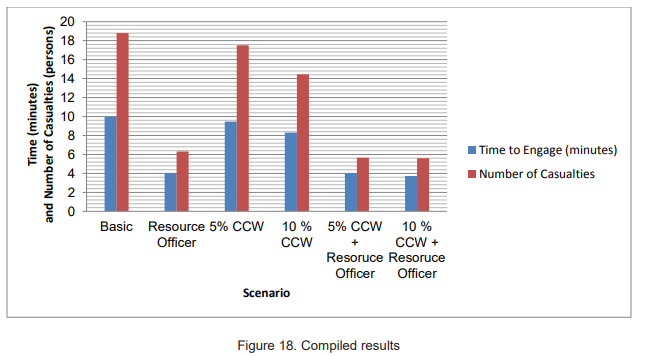

Additionally, in 2014, Charles Anklam, Adam Kirby, Filipo Sharevski, and Dr. J. Eric Dietz published an article titled “Mitigating Active Shooter Impact: Analysis for Policy Options Based on Agent/Computer-Based Modeling” in the Journal of Emergency Management. In this article, the authors explored four potential scenarios for responding to an active shooter situation in a public school setting using agent-based computer modeling techniques. These scenarios include:

- The basic scenario, where no access control or security measures are employed within the school.

- The scenario assuming the presence of concealed carry individuals (5-10 percent of the workforce) in the school.

- The scenario where the school has assigned a resource officer.

- The scenario in which the school has both a resource officer and concealed carry individuals (5-10 percent) present within the school.

The study’s findings indicate that reducing response time is crucial for minimizing casualties. According to the model data, the most effective approach to achieve this is by having armed personnel on-site at the school who can confront the active shooter before law enforcement arrives. This approach’s efficiency is further enhanced by having both armed resource officers and armed teachers or staff members equipped with concealed weapons, allowing them to engage the shooter should the threat enter their vicinity. Consequently, the data suggests that when teachers and faculty act as a static deterrent and respond defensively without engaging the shooter directly, having a greater number of armed teachers or staff members leads to a significant reduction in casualties.

Homeland Security had developed a booklet regarding active shooter events. According to the booklet:

Good practices for coping with an active shooter situation

- Be aware of your environment and any possible dangers

- Take note of the two nearest exits in any facility you visit

- If you are in an office, stay there and secure the door

- If you are in a hallway, get into a room and secure the door

- As a last resort, attempt to take the active shooter down. When the shooter is at close range and you cannot flee, your chance of survival is much greater if you try to incapacitate him/her.

CALL 911 WHEN IT IS SAFE TO DO SO!

“Courage is not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. It is a virtue that enables us to face adversity and take action despite our inner apprehensions.” – Plato

(3) Extra

Reeping, P. M., Jacoby, S., Rajan, S., & Branas, C. C. (2019) published the article Rapid response to mass shootings at the Criminology & Public Policy, which is a review of 34 other articles regarding active shooters. The authors stablished 10 recomendations based on their findings, as follows:

- Understand that firearm injury is a “surgical disease” and that the faster someone who has been seriously shot gets to a designated trauma center hospital operating room, the better (Carr, Caplan, Pryor, & Branas, 2006).

- Conduct large-scale trainings of police, educators, and the public in hemorrhage control, taking care not to expose young children to trainings designed for adults. Hemorrhage kits can be kept in areas where crowd sizes are large.

- When arriving at the scene of a mass shooting, police, EMS and other first responders should form an integrated command center. To the extent possible, transport of seriously injured people to a trauma center hospital should be a first priority by whichever public safety professionals are first to arrive on scene and can safely transport.

- After being appropriately trained, police should be permitted to triage and transport people who have been seriously injured in a mass shooting to a designated trauma center hospital, without waiting for EMS personnel. Jurisdictions should establish direct police-to-hospital transport polices and dedicate equipment and training in support of these policies. REEPING ET AL. 309

- Police and EMS professionals should be thoroughly trained in systematic procedures for accurately triaging people in mass shootings. Simulations and virtual trainings can help prepare these public safety professionals for mass shooting events and triage.

- With proper training, equipment, and support from police, EMS professionals can safely be brought into the “warm zone” near a mass shooting and begin to transport and administer medical support sooner than they otherwise would be able to.

- Before the first seriously injured people arrive at their emergency departments from a mass shooting, all hospitals should follow the team-based model used at trauma centers and be well prepared in advance to receive these patients. This can be expedited using closed-channel, public safety communication systems that have been tested and prepared in advance, although disaster response coordinators and hospital managers are also encouraged to monitor social media for unplanned patient surges.

- Hospitals should not only be aware that they are likely to experience additional waves of severely injury patients from a mass shooting, but also be prepared in that these waves of additional people may be more severely injured than the first wave to enter the hospital (Carr et al., 2016).

- Hotlines can be established to better address concerns from family, friends, and the community and prevent overburdening of local communications systems.

- Medical and public safety systems should only direct appropriate responders onto the scene of mass shooting and discourage “good Samaritan” response from random members of the public, as well as from non-essential medical and public safety professionals who may be off-duty or coming from far away. Despite often being well-intended, mass casualty over-response is inefficient, creates congestion, and can dangerously impede evacuation and treatment (Carr et al., 2016).

(4) Final thoughts

Fighting against active shooters presents a formidable challenge. Various critical aspects need to be carefully addressed, including preventive measures, prompt detection, the design and implementation of facilities aimed at minimizing casualties, and, of course, the actual confrontation itself.

For a comprehensive understanding of attacker behavior, numerous articles delve into the subject, offering insights and practical strategies based on evidence. However, it is undeniable that courage and a commitment to safeguarding others will forever remain essential. Emphasizing the importance of being constantly prepared and equipped, it becomes evident that readiness is an ongoing necessity in the face of potential threats.

This material obviously does not exhaust the topic, which can be virtually infinite, but it can provide the foundations to help citizens prepare to face threats. It is always recommended to continually study the subject and, of course, engage in constant training focused on armed combat.

References

Anklam, Charles & Kirby, Adam & Sharevski, Filipo & Dietz, J.. (2014). Mitigating Active Shooter Impact; Analysis for Policy Options Based on Agent/Computer Based Modeling. Journal of emergency management (Weston, Mass.). 13. 10.5055/jem.2015.0234.

Briggs, T. W., & Kennedy, W. G. (2016, December). Active shooter: An agent-based model of unarmed resistance. In 2016 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC) (pp. 3521-3531). IEEE.

Floyd, K. H., Montes, J., Pianka, J., & Quirarte, J. S. (2018). Victim Services Best Practices: The Aftermath of a Mass Violence Incident. Annotation.

Homeland Security https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-03/fema_faith-communities_active-shooter.pdf

Homeland Security https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/active_shooter_booklet.pdf

Kanehisa, Rodrigo & Neto, Areolino. (2019). Firearm Detection using Convolutional Neural Networks. 707-714. 10.5220/0007397707070714.

Lacey N. Wallace, Responding to violence with guns: Mass shootings and gun acquisition, The Social Science Journal, Volume 52, Issue 2, 2015, Pages 156-167, ISSN 0362-3319, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2015.03.002.

Nyberger, K., Strömmer, L., & Wahlgren, C. M. (2023). A systematic review of hemorrhage and vascular injuries in civilian public mass shootings. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 31(1), 30.

Smith, Edward Reed MD; Shapiro, Geoff EMT-P; Sarani, Babak MD The profile of wounding in civilian public mass shooting fatalities, Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery: July 2016 – Volume 81 – Issue 1 – p 86-92

doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001031

Reeping PM, Jacoby S, Rajan S, Branas CC. Rapid response to mass shootings: A review and recommendations. Criminol Public Policy. 2020;19:295–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12479

Zhu, R., Lucas, G.M., Becerik-Gerber, B. et al. The impact of security countermeasures on human behavior during active shooter incidents. Sci Rep 12, 929 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04922-8