For quite some time, it seems to have become a trend for shooters worldwide to perform their sequence of shots during training, followed by a nodding of their heads from side to side, known as scanning. However, for the majority of practitioners, this process has become purely mechanical, lacking a true understanding of its origin and objectives. This has turned the activity into a somewhat futile exercise.

In today’s discussion, we will delve into two post-shooting procedures known as tactical follow-through and scanning.

Post-shooting procedures aim to organize routines immediately following a lethal encounter. Their practice should primarily reduce the shooter’s risks when exposed to a dangerous scenario. Training should condition armed citizens not to remain static after facing a threat, instilling a pre-established motor repertoire for moments of high stress.

1) Tactical Follow Through

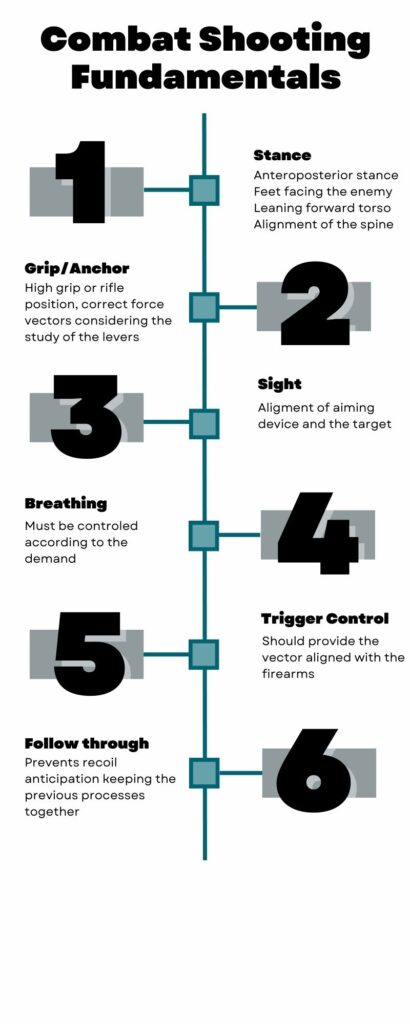

While technical follow-through is the sixth shooting fundamental, it should not be confused with tactical follow-through, which is a post-shooting procedure. Tactical follow-through was likely implemented to correct common training errors, such as the practice of double taps or improper firearm positioning after a shot.

The concept of tactical follow-through involves assessing the effectiveness of the shots fired, visually confirming whether the enemy still poses any level of danger. Typically, this is done while keeping the weapon pointed at the enemy, enabling a quick engagement and shot if necessary.

2) Scanning

Among the various physiological reactions to stress, the well-known tunnel vision occurs. This means that during a high-arousal event, the individual stops processing peripheral visual information, focusing all cognition on the central part of their visual field.

In combat, the environment is often unknown and constantly changing. Therefore, it is wise for the shooter to constantly reassess additional information outside the main threat, searching for new enemies or risks. To address this, instructors guide their students to turn their heads from side to side, forcing continuous visual field and information processing. This initial solution tackles two problems: (a) tunnel vision and (b) maintaining the line of fire, as the weapons stay pointed forward, and only the shooter’s head turns. In other words, maintaining muzzle control.

Recommendations

In preparing the shooter for omnidirectional combat, we suggest incorporating the following points into training routines from the foundation, increasing the likelihood of success in armed confrontations:

(a) Avoid conditioning to the practice of double taps. Instead, practice firing “as many times as necessary” to eliminate the threat.

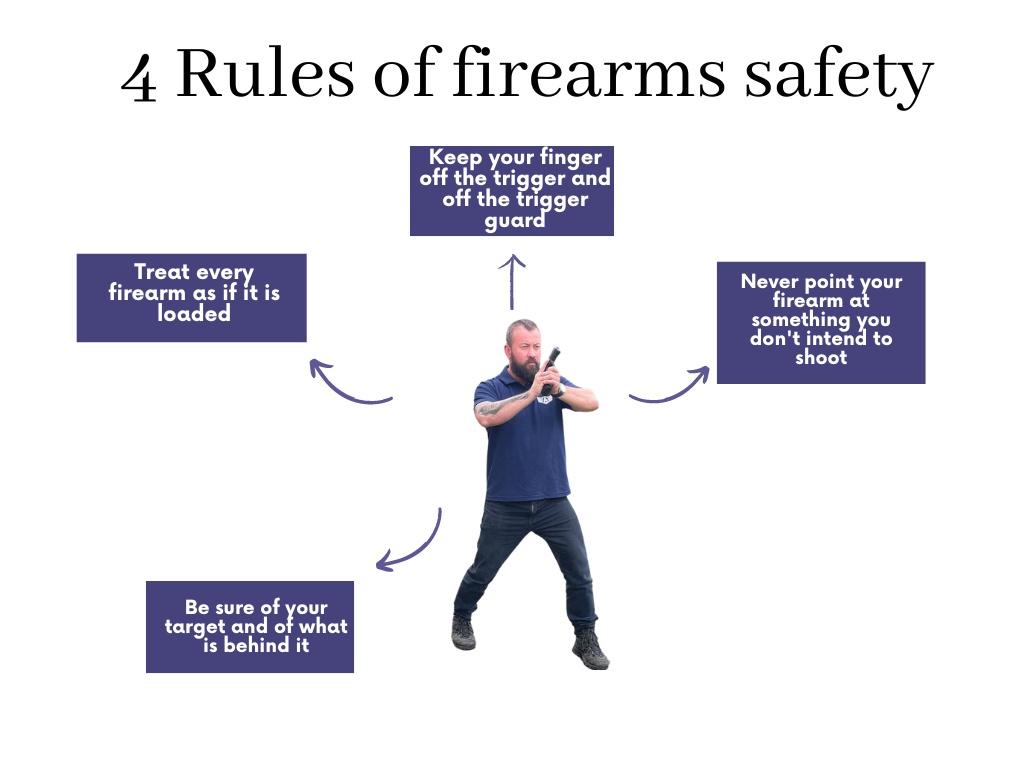

(b) Understand the proper application of muzzle control and weapon retention techniques, creating training scenarios where these skills are exclusively utilized.

(c) From the foundation, ensure the shooter can move in 360° with their firearm without compromising safety rules.

(d) Avoid mechanizing the scanning process. Propose involving the entire body of the shooter in a 360° scan.

(e) Remember that post-shooting procedures are all useless if the main element—the shot—has not been adequately trained and executed.